Social media channels and private messaging groups are being used in Russia to recruit a new brigade of mercenaries to fight in Ukraine alongside the army, the BBC has learned.

The BBC has spoken to a serving mercenary and a former fighter with close links to one of Russia’s leading mercenary organisations, who have shared details of the recruitment campaign.

The serving mercenary said many veterans of the secretive Wagner organisation were contacted on a private Telegram group a few weeks before the start of the war. They were invited to a “picnic in Ukraine”, with references to tasting “Salo”, a pork fat traditionally eaten in Ukraine.

The message appeals to “those with criminal records, debts, banned from mercenary groups or without an external passport” to apply. The message also included that “those from the Russian-occupied areas of Luhansk and Donetsk republics and Crimea – cordially invited”.

IMAGE SOURCE,@RSOTM TELEGRAM GROUP Image caption,Wagner in eastern Ukraine, 2014/15

IMAGE SOURCE,@RSOTM TELEGRAM GROUP Image caption,Wagner in eastern Ukraine, 2014/15The Wagner group is one of the most secretive organisations in Russia. Officially, it doesn’t exist – serving as a mercenary is against Russian and international law. But up to 10,000 operatives are believed to have taken at least one contract with Wagner over the past seven years.

The serving mercenary who spoke to the BBC said new recruits are being placed in units under the command of officers from the GRU, the Russian military intelligence unit of the ministry of defence.

He stressed that the recruitment policy had changed, and fewer restrictions were applied. “They are recruiting anyone and everyone,” he said, unhappy with what he described as the lower professionalism of the new fighters.

He said the new units being recruited are no longer referred to as Wagner, but new names – such as The Hawks – were being used.

This seems to be part of a recent tendency to steer away from the Wagner group’s reputation, as “the brand is tainted”, says Candace Rondeaux, professor of Russian, Eurasian and Eastern European studies at Arizona State University.

Wagner has faced repeated accusations of human rights abuses and war crimes in its operations in Syria and Libya.

The mercenary sources who spoke to the BBC, said the recruits are trained at the Wagner base in Mol’kino in southern Russia, next to a Russian army base.

As well as the private messaging groups, there has also been a public campaign in Russia to recruit mercenaries.

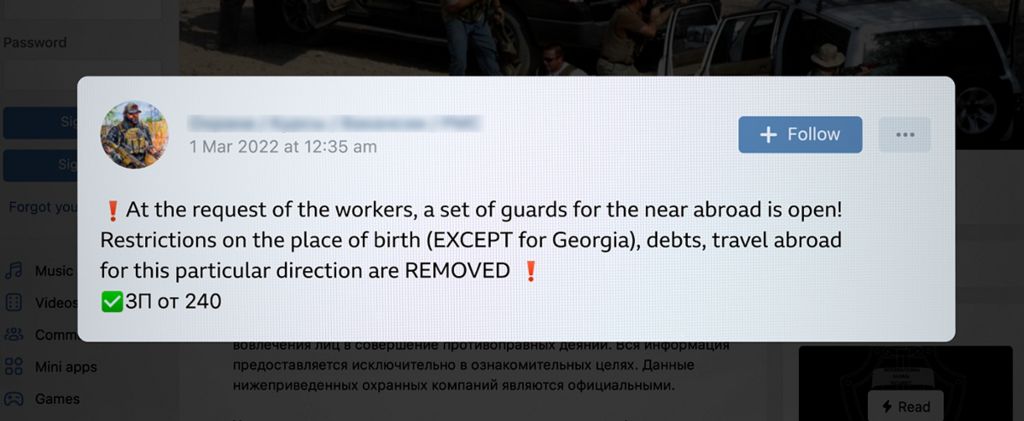

On the Russian social media platform VK, a page that describes itself as a specialist in security activities, posted an advert during the first week of the invasion calling for “security guards” from other former Soviet Union countries to apply for “the near abroad”. Military experts have said this is a reference to Ukraine.

Previously, a criminal record was a block for those wanting to join the mercenaries. Also restrictions were placed on anyone born outside Russia because of doubts around loyalty.

IMAGE SOURCE,VK SOCIAL MEDIA SITE Image caption,Translated advert for mercenaries on the VK social media site

IMAGE SOURCE,VK SOCIAL MEDIA SITE Image caption,Translated advert for mercenaries on the VK social media siteThere is a “high demand on fighters” and to make a difference on the ground “they’re going to need thousands of mercenaries”, says Jason Blazakis, senior research fellow at the Soufan Centre, a US-based security think tank.

On Friday, the Russian defence minister Sergei Shoigu said that 16,000 fighters from the Middle East had volunteered to fight with the Russian army. The Russian president Vladimir Putin gave orders allowing fighters from the Middle East to be deployed in the war.

It has been reported that up to 400 fighters from the Wagner group have been in Ukraine.

The Wagner group was first identified in 2014, when it was backing pro-Russian separatists in the conflict in eastern Ukraine.

The serving Wagner fighter explained that in the first days of the invasion of Ukraine he was sent to the country’s second city, Kharkiv, where he said his unit successfully completed a mission without revealing what it was.

“We were then paid $2,100 (£1,600) for a month’s work and returned home,to Russia,” he told the BBC.

IMAGE SOURCE,@RSOTM TELEGRAM GROUP Image caption,Wagner members in Syria

IMAGE SOURCE,@RSOTM TELEGRAM GROUP Image caption,Wagner members in SyriaBlazakis describes using mercenaries as a “sign of desperation” to keep the Russian public’s support. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has stirred several protests In Russia. Thousands have been arrested. Blazakis added that using mercenaries allows the Kremlin to “keep the death toll down because mercenaries are used like cannon fodder”.

Moscow has always denied any links with mercenary groups.

The BBC asked the Russian ministry of defence whether the base in Mol’kino was being used to recruit additional forces for what the Russian authorities call “a special military operation in Ukraine”. No response was received.

BBC