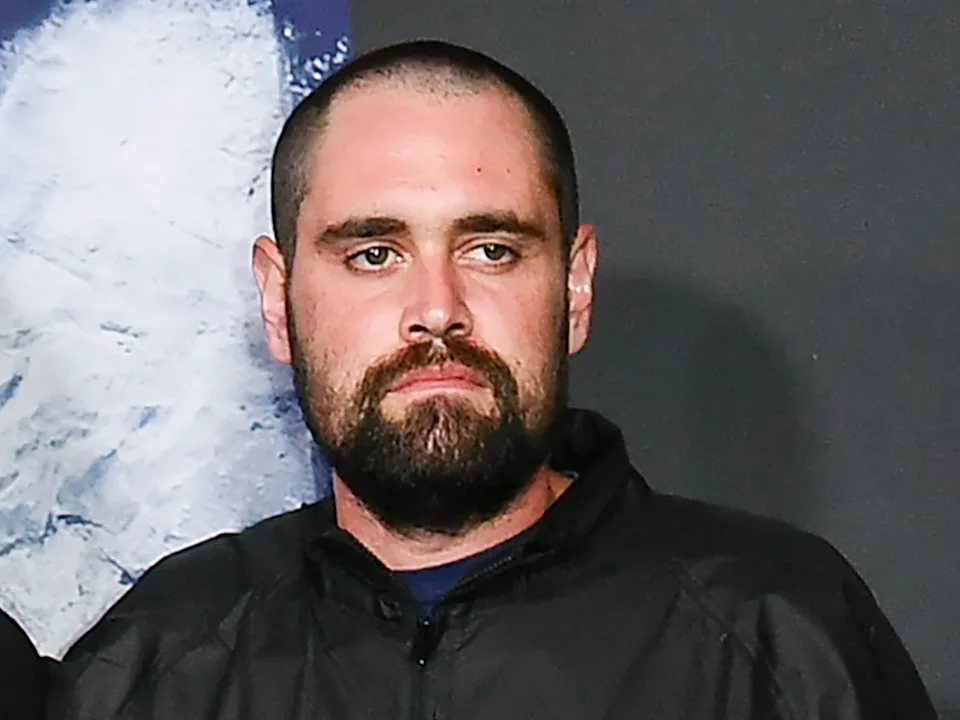

More than 42 years after the deadly bombing of a Paris synagogue, a court in Paris has convicted a Lebanese-Canadian university professor of carrying out the attack.

The judges decided that Hassan Diab, 69, was the young man who planted the motorcycle bomb in the Rue Copernic on 3 October 1980.

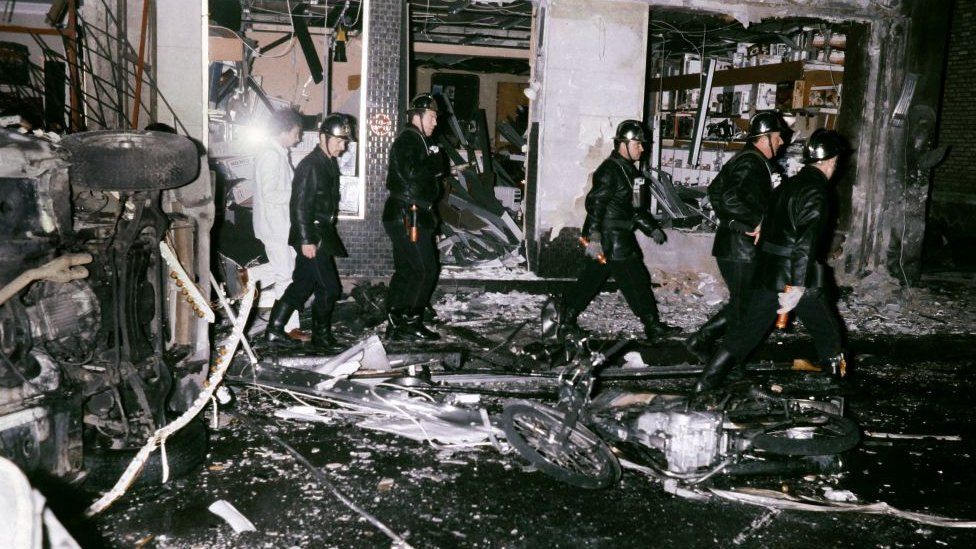

Four people were killed and 38 others wounded in the bombing.

Diab called his situation “Kafkaesque”, Canadian media reported.

He refused to attend the trial but the judges gave him a life sentence.

Prosecutors had argued it was “beyond possible doubt” that he was behind the bombing. His supporters have condemned the trial as “manifestly unfair”.

The Rue Copernic attack was the first to target Jews in France since World War Two, and became a template for many other similar attacks linked to militants in the Middle East in the years that followed.

The decades-long investigation became a byword both for protracted judicial confusion, as well as for the dogged determination of a handful of magistrates not to let the case be forgotten.

Diab is a Lebanese of Palestinian origin who obtained Canadian nationality in 1993 and teaches sociology in Ottawa.

He was first named as a suspect on the basis of new evidence in 1999, already nearly 20 years after the killings.

Eight years later the French issued an international arrest warrant, and it was not until 2014 that Canada agreed to extradite. But in 2018 French magistrates declared the case closed for lack of proof, allowing Diab to return to Canada.

Finally in 2021 an appeal against the closure of the case was upheld in the Supreme Court, the first time this had ever happened in a French terrorism case.

It meant a trial could finally go ahead, and it began earlier this month.

From the start Diab, protested his innocence and he did not return to France for the trial, which was conducted in his absence. His conviction means that a second extradition request will have to follow, though with strong doubts over whether it will succeed.

According to the Canadian Press news agency, Diab said on Friday that “we hoped reason would prevail”.

Responding to the verdict, the Hassan Diab Support Committee in Canada called on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to make it “absolutely clear” that no second extradition would be accepted.

They said 15 years of legal “nightmare… is now fully exposed in its overwhelming cruelty and injustice”.

At a news conference, Mr Trudeau said his government “will look carefully at next steps, at what the French government chooses to do, at what French tribunals choose to do”.

“But we will always be there to stand up for Canadians and their rights,” he added.

Over three weeks the court heard an account of the known facts of the case, plus arguments identifying Diab as the bomber and counter-evidence suggesting he was a victim of mistaken identity.

None of the original investigating team was alive to speak, and the surviving witnesses who saw the attacker in 1980 all admitted that after more than 40 years their memories were too hazy to be reliable.

The bomb was left in the saddle-bag of a Suzuki motorbike outside a synagogue in the wealthy 16th arrondissement of Paris. Had there not been a delay, the pavement would have been packed with people leaving the religious service inside.

In 1980 the investigation initially centred on neo-Nazis, and there were mass demonstrations by the political left. But a claim by an ultra-right group was found to be fake, and by the end of the year attention had switched to a Middle East connection.

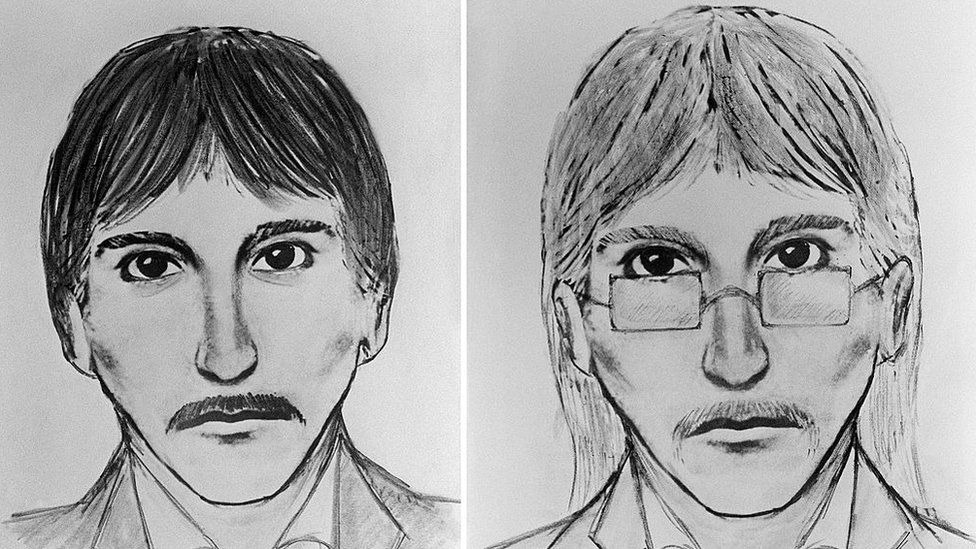

The bomber was identified as having a fake Cypriot passport bearing the name Alexander Panadriyu.

He was believed to have entered France from another European country as part of a larger group, and to have bought the motorbike at a shop near the Arc de Triomphe.

He was thought to belong to a dissident Palestinian group called the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-Special Operations (PFLP-SO).

But the investigation hit a wall, and it was not till 1999 that Hassan Diab’s name emerged from new information, believed to emanate from the former Soviet bloc.

Italian authorities then revealed that in 1981 the passport of a Hassan Diab had been found at Rome airport in the possession of a senior figure from the PFLP-SO. The passport bore stamps showing the holder entering and leaving Spain around the dates of the Rue Copernic attack.

The core of the prosecution case rested on the passport.

Under questioning while in custody, Diab explained that he had lost the passport just a month before the attack. But in Lebanon a French judge found an official declaration for the lost passport – a declaration made in 1983 and with a date of loss in April 1981.

The defence argued that all of this was circumstantial, and that there was still no hard evidence that Diab was in France in October 1980. They produced testimony from friends in Beirut who said Diab had been sitting university exams at the time of the attack.

Handwriting analysts who said the hotel registration form signed by the attacker was consistent with Diab’s script were also dismissed as inconclusive.

“The only decision that is juridically possible – even if it’s on a human level a difficult one – is acquittal,” defence lawyer William Bourdon said in his summing-up Thursday. “I am here before you to prevent a judicial error.”

But prosecutor Benjamin Chambre, while regretting that all the other members of the terrorist group had escaped without charge, said: “With Hassan Diab, we have the bomb-maker and the bomb-planter. That’s already something.”