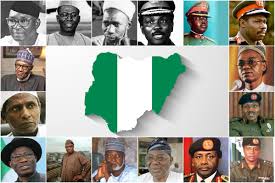

Nigeria had its worst economic growth rate since independence right before Muhammadu Buhari, then an army major general, overthrew late President Shehu Shagari in a coup d’état on December 31, 1983, resulting from the worldwide economic crisis of the 1980s.

Mr. Buhari, who was deposed after only 20 months in charge, presided over the country’s fastest GDP growth rate ever, according to World Bank figures.

When he took leadership, the GDP growth rate was -10.92 percent. However, it was 5.91 percent at the time he was removed. That represented a rise of 16.83 percentage points.

Nigeria has only ever approached that level of development under the rule of Murtala Muhammed, an army commander slain in an unsuccessful coup in his seventh month in office on February 13, 1976.

Mr. Muhammed’s predecessor, Yakubu Gowon, the nation’s longest-serving military commander (August 1, 1966 – July 29, 1975), stepped down following a period of oil glut and a -5.23 percent economic growth rate. Growth had risen to 9.04 percent by the time Mr. Muhammed was slain, a 14.27 percentage point gain.

Mr. Muhammed’s deputy and successor, Olusegun Obasanjo, was unable to maintain that level of growth, and when he left office in 1979, the pace had fallen to 6.59 percent. When he returned as a democratically elected president in 1999, some 20 years later, he made amends.

Growth increased from 0.58 to 6.59 percent over his eight years as civilian president, a 6.01 percentage point increase and the third-best since independence.

The First Republic led by Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa also saw a growth jump from 1.89 percent in 1960 to 4.89 percent in 1965.

Sani Abacha, under whose brutal rule Nigeria became an international pariah, recorded the fourth-highest GDP growth, taking it from -1.81 percent in 1993 when he toppled Ernest Shonekan, to 2.58 percent when he died in office. This amounts to a 4.39 percentage point rise in five years.

The Nigerian government cited this record as well as the fall in the inflation rate from 54 percent to 8.5 percent between 1993 and 1998 for naming Mr. Abacha, whose regime earned $64 billion from oil, according to OPEC, as a posthumous recipient of Nigeria’s centenary awards in 2014.

The citation said the Abacha regime “oversaw an increase in the country’s foreign exchange reserves from $494 million in 1993 to $9.6 billion by the middle of 1997, and reduced the external debt of Nigeria from $36 billion in 1993 to $27 billion in 1997.”

As president for three years (2007-2010), Mr. Obasanjo’s democratic successor, Umaru Yar’Adua, grew the economy from 6.59 to 8.01 percent (a 1.42 percentage point rise).

Messrs Obasanjo and Yar’Adua’s economic successes have been linked to high oil revenues, with Nigeria earning $261.8 billion and $139.6 billion respectively under both administrations, according to OPEC.

Only Goodluck Jonathan’s administration earned more revenue from oil with $381.9 billion. However, Mr. Jonathan could not sustain the 8.01 percent growth rate he met when he became president in 2010. He left office in 2015 with a growth rate of 2.65 percent.

Mr. Shonekan, who headed an interim government after the Ibrahim Babangida junta resigned, was the country’s leader in a year that saw negative growth drop from -2.04 percent in 1993 to -1.81 percent in the year that followed. By the time Mr. Abacha overthrew him, percentage point growth was 0.23.

Overall, since independence, Nigeria recorded its highest GDP growth year-on-year in the late 70s under Mr. Gowon, shortly after the civil war that quelled the Biafra secession bid and left millions dead.

Growth peaked at 25 percent in 1970, rising from the 24.2 percent growth in the previous year. In 1971, the rate fell sharply to 14.2 percent, and not until 2002, under Mr. Obasanjo, did Nigeria record annual GDP growth of 15.3 percent again.

In 1990, with Mr. Babangida at the helm, growth was 11.8 percent. In 1974, it was 11.2 percent. Only in 2004 was expansion up to 9.3 percent.

The boom of the 1970s was helped by an oil price bubble that brought tremendous earnings to the country.

President Buhari’s current term has seen the country’s growth rate dip by 0.41 percentage points (from 2.65 percent to 2.21 percent), and he has led the country into and out of two recessions, owing to oil price slumps and the Covid-19 outbreak.

Like him, Mr. Gowon (from -4.25 percent to -5.23 percent), Abdulsalami Abubakar (from 2.58 percent to 0.58 percent), Mr. Obasanjo (during his first coming from 9.04 percent to 6.76 percent), Mr. Jonathan (from 8.01 percent to 2.65 percent), Mr. Babangida (from 5.91 to -2.04), Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi (from 4.89 percent to -4.25 percent) and Shehu Shagari (from 6.76 percent to -10.92 percent) all oversaw decelerations in economic growth.

In terms of average GDP growth, Murtala Muhammed (9 percent), Olusegun Obasanjo (7.7 percent as democratic president), Musa Yar’Adua (7.6 percent), Yakubu Gowon (6.8 percent), and Goodluck Jonathan (5 percent) ranked highest.

The tenures of Messrs Shonekan (-1.8 percent), Aguiyi-Ironsi (-4.3 percent), and Shagari (-6.7 percent) averaged negative growth.

Judging by their percentage increase rates, Messrs Obasanjo (as civilian president with 1036.2 percent), Muhammed (272.8 percent), Abacha (242.5 percent), Buhari (as head of state with 154.1 percent), Yar’Adua (21.5 percent), and Shonekan (11.3 percent) respectively had the highest improvements.

Others saw a drop in percentage, with Messrs. Abubakar, Babangida, and Obasanjo (as military dictator) having the worst statistics.

GDP growth does not always reflect a population’s true standard of living, quality of life, or consumer purchasing power. Instead, per capita income (income per head), which is calculated by dividing GDP by the population, is used to estimate the average amount in each person’s pocket in a country.

Ada Peter