Security experts have warned that Nigeria may be running out of time to prevent extremist violence from spilling into major South-West cities following last week’s mass killings in Kwara State, as states in the region begin tightening border security.

The warning comes after coordinated attacks on Woro and nearby communities in Kaiama Local Government Area, where at least 176 residents were reportedly killed—one of the deadliest incidents in Kwara’s history. Analysts say the assault signals a dangerous expansion of insurgent activity beyond its traditional North-East base.

According to military and counter-terrorism sources, Boko Haram splinter factions and allied armed groups are increasingly operating from the Kainji National Park corridor, exploiting the vast, poorly governed forest that stretches across Kwara and Niger states. The area lies barely 90 kilometres from Ilorin and less than 400 kilometres from Lagos, raising fears of proximity to Nigeria’s economic and population hubs.

Security strategists say insurgents displaced by sustained military pressure in the North-West and North-East have regrouped in the park, transforming it from a wildlife reserve into a strategic hideout. The 5,340-square-kilometre terrain of dense forest, savannah and rocky outcrops provides cover for jihadist factions, bandits and organised criminal networks.

Analysts estimate that the scale of violence linked to insurgent commander Abubakar Saidu, also known as Sadiku, in a single week in Kwara rivals casualty figures from major Boko Haram attacks recorded in the North-East in 2025. They warn that without a coordinated, intelligence-led operation across the Kwara–Kogi–Niger axis, militants could entrench themselves, activate sleeper cells and move along forest routes into the South-West.

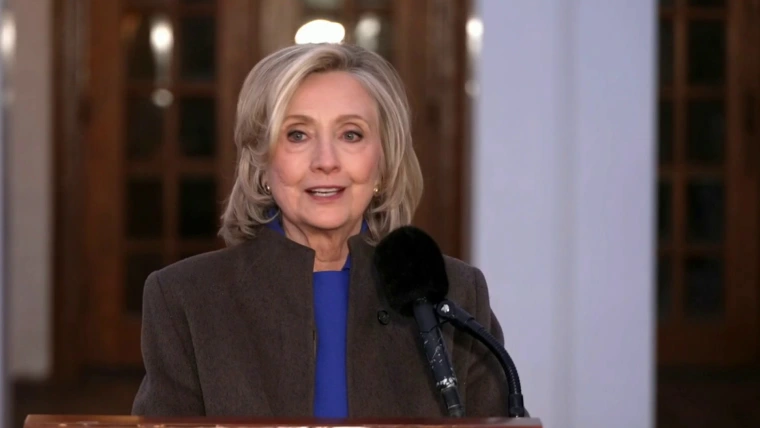

Former Troop Commander and ex-Director of ICT at the Nigerian Army Signals Headquarters, Maj.-Gen. Peter Aro (retd.), cautioned against viewing the threat through a conventional military lens. He described Woro’s closeness to Ilorin as a critical warning sign.

“Terror groups do not move suddenly; they advance gradually. They establish sleeper cells, spy on communities, map routes, test response times and exploit weak governance before launching major attacks,” Aro said.

He warned that evidence of sleeper cells near the South-West would mean infiltration had already begun, stressing that forest belts, border towns and transport corridors must now be prioritised. Aro singled out Ondo State as especially exposed due to extensive forests and limited rural surveillance.

“Terrorism spreads quietly before it explodes. Nigeria still has time to stop gradual infiltration into the South-West, but denial and delay will only raise the cost,” he added.

Aro also noted that the onset of heavy rains could further complicate military access, as thick vegetation and flooded tracks would make the Kainji forest harder to penetrate, effectively shielding insurgents.

Former Chief of Defence Training and Planning, Maj.-Gen. Ishola Williams (retd.), criticised Nigeria’s counter-terrorism approach, arguing that tactics had remained unchanged for more than a decade despite worsening outcomes.

“How can small groups of 200 attackers overrun communities and kill people without resistance? Are we not shamed?” Williams asked, questioning the effectiveness of past international support and joint operations.

He also raised accountability concerns, alleging that warnings had sometimes been issued ahead of attacks but not acted upon. “In a well-organised country, people would resign or be sacked for such failures. Are we accountable in Nigeria?” he queried.

A retired Assistant Commissioner of Police, Segun Onifade, described the situation around Kainji National Park as a symptom of Nigeria’s inability to secure vast rural spaces. He called for permanent joint military, police and intelligence bases within and around the park.

“Forest access routes must be controlled, illegal mining camps dismantled and local informant networks disrupted,” Onifade said, advocating armed ranger units, drones and satellite surveillance. “Protected forests can no longer be treated as neutral ecological spaces. They are now frontline security zones.”

Once home to ranger outposts and wildlife conservation infrastructure, the park has suffered years of neglect, leaving large areas ungoverned. Security analyst Abdulyekeen Mohd Bashir said this vacuum allowed militants pushed out of Zamfara and other North-West theatres to regroup.

“Terrorists dislodged from Zamfara and other North-West theatres regrouped in Kainji because it was loosely secured,” he said, adding that Boko Haram factions, JNIM-linked elements and bandit groups now operate in the corridor.

Another analyst, Akeem Olatunji, said the Kaiama attack exposed serious weaknesses in early-warning systems. “Warnings were issued, quickly dismissed, and everyone went to sleep until the attackers struck,” he said.

Questions have also been raised over the non-deployment of air assets. Security sources confirmed that the Nigerian Air Force’s 407 Air Combat Training Group in Kainji—where A-29 Super Tucano jets acquired under former President Muhammadu Buhari were stationed—is located about 10 minutes by air from Woro.

“Some of those fighter jets bought during the Buhari era were at the 407 Air Combat Training Group base in Kainji,” a senior security source said. “From there, it is about 10 minutes by air to Woro, where the attack happened.”

A civil society group, the Foundation for Peace Professionals, questioned why air power was not used during the attack. Its Executive Director, Abdulrazaq Hamzat, asked: “Why didn’t the government deploy the Air Force to prevent the attackers from completing their operation while the attack was ongoing?”

Hamzat warned that the Kainji corridor linking Niger, Kebbi and Kwara states had become a low-risk operating environment for armed groups due to weak coordination and multiple escape routes.

As fears of southward expansion grow, Lagos and Osun states say they have stepped up security. Lagos State Commissioner for Information and Strategy, Gbenga Omotosho, said intelligence gathering had been intensified through the Lagos Neighbourhood Safety Corps, with plans to recruit 1,500 additional operatives.

“Security is everybody’s responsibility, not just the government’s,” Omotosho said, noting increased support for the Rapid Response Squad and closer collaboration with neighbouring South-West states.

In Osun, the Special Adviser on Security to the Governor, Samuel Ojo, said the state’s boundary with Kwara had been reinforced. “As I am talking with you, our boundaries with Kwara have been fortified with more security personnel,” he said, adding that residents had been urged to report suspicious movements.

Meanwhile, Kwara State Governor Abdulrahman Abdulrazaq confirmed the deployment of senior security officers, including the GOC of the Army’s 2 Division and a Deputy Inspector-General of Police. He said troops had been deployed and Operation Savannah Shield activated, following a condolence visit by Vice President Kashim Shettima to Kaiama.

With Nigeria’s terror map shifting southward, analysts warn that decisive action around the Kainji axis could determine whether the violence is contained—or allowed to edge closer to the heart of the South-West.