Georgia is facing a precarious moment.

After enjoying years of relative stability, this small, stunningly beautiful country—nestled between the Black Sea’s pale beaches and the snow-dusted Caucasus mountains—is at a crossroads, risking a slide back into political instability or even chaos reminiscent of its early post-Soviet years.

The future of Georgia hangs in the balance. Will this strategically vital nation, with its crucial ports and pipelines, continue on a path towards full membership in NATO and the European Union, akin to the Baltic states? Or will political turmoil, rigged elections, and the barely concealed influence of Russia pull Georgia back into Moscow’s authoritarian sphere, like Belarus?

Two major factors are driving the current situation: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the rise of anti-Western, populist, and nationalist rhetoric, which has proven effective and politically polarizing in parts of Eastern Europe and beyond.

Georgia—a nation with a rich history and culture, and a strong desire to strengthen ties with Europe, grow its economy, and avoid a return to the separatist wars and conflicts of the 1990s—is now unexpectedly divided in sharp new ways.

On one side stands a massive street protest movement, increasingly dominated by young Georgians. This movement is characterized by youthful exuberance, ranging from mocking memes about the prime minister’s haircut to energetic dancing, and highly organized medical students ready to respond to those injured in clashes with the police.

Georgia’s youth, galvanized by the desire to join the EU and radicalized by events in Ukraine, have injected new energy into opposition protests against a deeply controversial new law.

The law, passed by parliament and then vetoed by the president, is expected to come into force soon despite the veto. It mirrors a similar law introduced in Russia and appears aimed at labeling many civil society groups as “foreign agents.”

As written, the law would almost certainly derail Georgia’s goal of EU membership.

“It kills Georgia’s European future,” warned Salome Samadashvili, an opposition MP and former ambassador to the EU. “That’s why this is the most important moment in Georgia’s modern history. If, at the next elections, we manage to get rid of this government and build a strong pro-European coalition, then Georgia can move forward and our future can be irreversible.”

However, October’s elections seem a distant prospect amid widespread fears of more violent confrontations in the capital, Tbilisi.

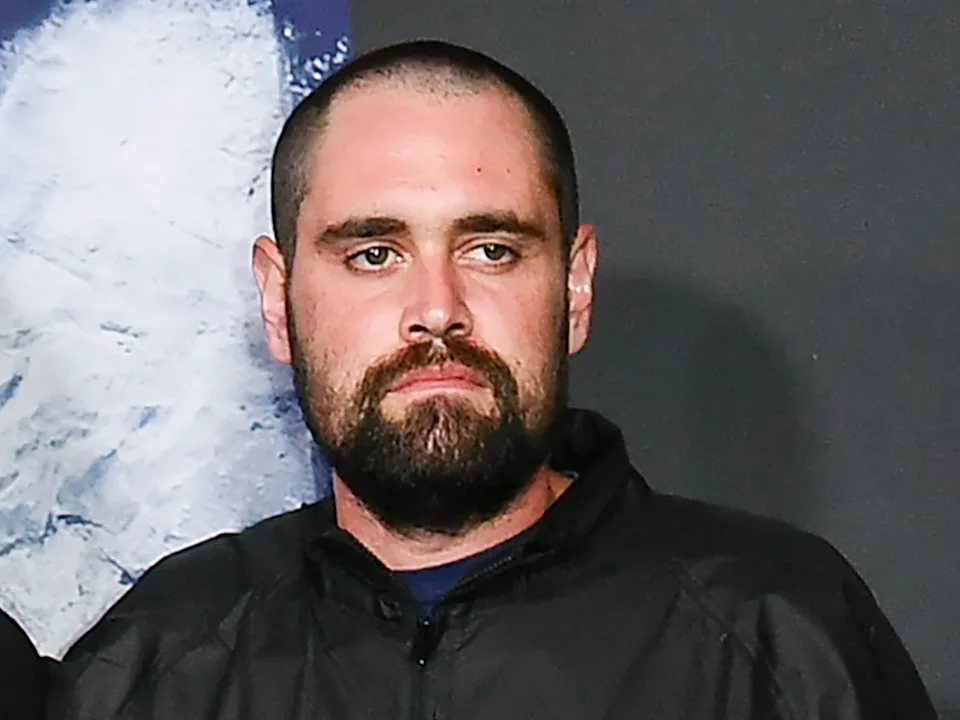

“We see that our government escalates this situation. I think the aim is to initiate civil confrontation. If we lose, we lose our country, our freedom, our independence. We become part of Russia,” said David Katsarava, a prominent activist currently in the hospital recovering from concussion and other injuries after being assaulted by police at a protest rally earlier this week.

Katsarava suffered a fractured eye socket and has visible strangulation marks around his neck. Other activists and opposition politicians report being targets of violence, abusive phone calls, threats, and intimidation.

Standing against the protest movement is Georgia’s government, backed by many supporters and increasingly forceful police and security forces.

The government maintains that its new “foreign agent” law is not influenced by Russia but aims to bring greater transparency to a poorly regulated and overly influential sector.

Officials have gone further, claiming that the protests are partly driven by meddling external forces from the West seeking to overthrow the government in a “coup d’état.”

As a result, relations between the Georgian government and the US and EU have sharply deteriorated in recent days.

Looking out over Tbilisi from a balcony on the top floor of city hall, Mayor Kakha Kaladze insisted that he and the governing party remained committed to a “European future” for Georgia and emphasized the need to find common ground with the protesters.