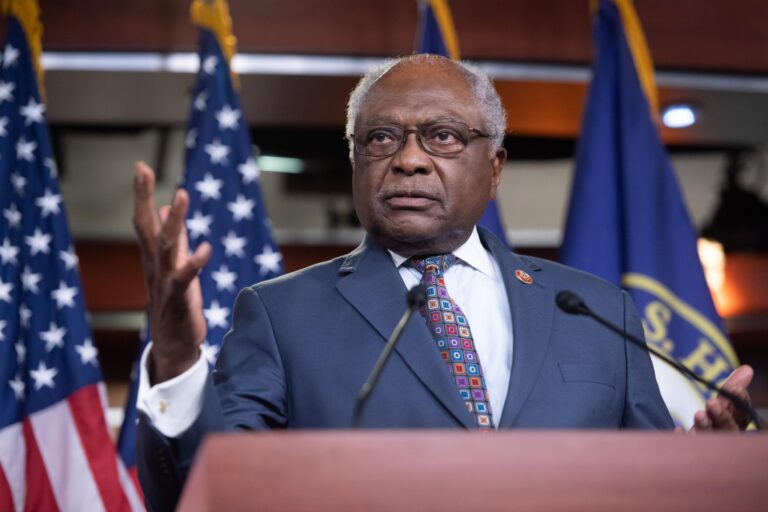

At President Joe Biden’s lowest moment in the 2020 campaign, South Carolina Rep. Jim Clyburn came to him with a suggestion: He should pledge to put the first Black woman on the Supreme Court.

After some cajoling, Biden made the promise at a Democratic debate, a move Clyburn credits with turning out the Black support that helped Biden score a resounding victory in the South Carolina primary and ultimately win the White House.

Two years later, the hoped-for vacancy on the court has arrived with the retirement of Justice Stephen Breyer. Biden is standing by his pledge. And Clyburn, the highest-ranking Black member of Congress, has another ask.

“Judge (Michelle) Childs has everything I think it takes to be great,” Clyburn said.

As the lobbying begins over filling the open court seat, Clyburn is harnessing his history with Biden and his stature as the No. 3 House Democrat to make a forceful case for his preferred choice, U.S. District Judge J. Michelle Childs, a jurist from his native South Carolina. It’s a campaign he’s making in public and in private, helping elevate Childs to an emerging short list of Black women who could soon make history.

In addition to Childs, early discussions about a successor include California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger, as well as Ketanji Brown Jackson, a former Breyer clerk who is now on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Biden is also looking at U.S. District Court Judge Wilhelmina Wright from Minnesota and Melissa Murray, a New York University law professor who is an expert in family law and reproductive rights justice.

For Biden, the court opening is a chance to show Black voters that he has not forgotten his promises to them, particularly after his failure this month to deliver on voting rights legislation in the Senate. He said Thursday that having a Black woman on the court is “long overdue” and that he would announce his choice by the end of February.

Clyburn had a head start. He began making his case for Childs more than two years ago.

In December 2020, just weeks after Biden won the White House, Clyburn said he wrote to the then-president elect advocating that Childs be promoted from South Carolina’s federal trial bench to the D.C. appeals court. A seat on court is often seen as a springboard for Supreme Court nominees.

“Everybody says, ‘Well, that’s the way you need to go, to go to the Supreme Court,‘” Clyburn said, of the appellate level. “I’ve never agreed to that, but you know, I don’t have to agree with all the rules that I have to play by.”

Last month, Biden officially submitted Childs’ name for an open slot on the circuit court. Her Senate hearing had been expected next week, which would have given Childs a closely watched audition of sorts, but staffers said Friday that had been delayed.

In interviews over recent days, Clyburn has argued that, if Childs were nominated, she could win the backing of South Carolina’s two Republican senators, Lindsey Graham and Tim Scott — an enticing prospect for Biden, offering the possibility of a pick that could satisfy the party and also win bipartisan support.

In a statement, Graham, a former Senate Judiciary Committee chairman, did not say whether he was open to voting for Biden’s choice. If Democrats are unified, he noted, they “have the power to replace Justice Breyer in 2022 without one Republican vote in support.”

A spokeswoman for Scott lauded Childs’ “respected reputation as a judge in South Carolina” and said “he looks forward to engaging with her if she is the nominee.”

Unlike most high court nominees, Childs isn’t an Ivy League graduate or a former federal appellate clerk. The 55-year-old graduated from the University of South Carolina School of Law. She also holds a master’s degree from the university’s business school, as well as a legal master’s from Duke.

Clyburn, who often pushed for ethnic and educational diversity among Biden’s Cabinet picks, said he felt Childs’ education outside the Ivy League, coupled with her upbringing in a single-parent household, would give the court an important perspective it is now missing.

“We run the risk of creating an elite society,” Clyburn told reporters. “We’ve got to recognize that people come from all walks of life, and we ought not dismiss anyone because of that.”

During years in private practice in Columbia, Childs became the first Black female partner at one of the state’s largest law firms, where she focused on employment and labor law. After several years as a state court judge, she was appointed to the federal trial bench. In 2014, before the Supreme Court ruled that gay couples had a right to marry nationwide, she ruled in favor of a gay couple seeking to have their District of Columbia marriage recognized in South Carolina.

All of her experiences, Clyburn said, give Childs the “ability to empathize”

Asked in a 2020 Q&A with her alma mater what advice she would give a young lawyer, Childs opined on the meaning of success, stressing the importance of becoming “a person of courage and conviction.”

“We all have a crucial role, individually and collectively, to be architects of society,” she said. “Being successful is not just for the purpose of a place of comfort and satisfaction, but a place of responsibility and challenge.”

Abc