More than two decades after the Supreme Court barred the execution of intellectually disabled individuals as “cruel and unusual punishment,” the justices on Wednesday began hearing a major case from Alabama that will determine how courts decide who qualifies as intellectually disabled — and how heavily IQ scores should factor into that determination.

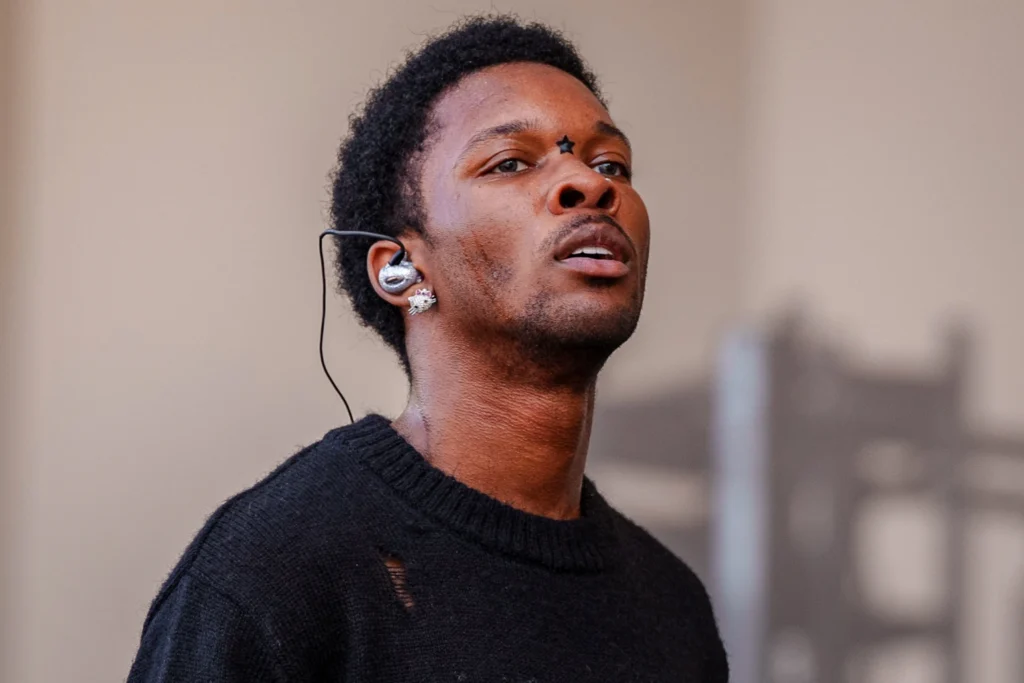

The case was brought by Joseph Clifton Smith, who confessed to a 1997 murder during a robbery but argues that his death sentence is unconstitutional because he has exhibited “substantially subaverage intellectual functioning” since childhood.

Over nearly 40 years, Smith has taken five IQ tests, scoring 75 (1979), 74 (1982), 72 (1998), 78 (2014), and 74 (2017). While an IQ below 70 is typically associated with intellectual disability, leading U.S. medical organizations emphasize that diagnosis requires a holistic evaluation, including assessments of social, adaptive, and practical skills — not test scores alone.

Experts note that IQ tests have a standard margin of error. Smith’s 1998 score of 72, for example, could fall to 69 once the three-point error range is applied, potentially placing him within the threshold for intellectual disability.

“Intellectual disability diagnoses based solely on IQ test scores are faulty and invalid,” attorneys for the American Psychological Association and American Psychiatric Association wrote in a brief to the court. “But IQ test scores remain relevant; IQ tests are a scientifically valid means to ascertain estimates of an individual’s intellectual ability. The key is to understand both the value of IQ tests and their limits.”

The Court’s eventual ruling could set a significant national standard, shaping how death penalty cases involving intellectual disability are evaluated across the country.