French President Emmanuel Macron is at risk of losing his outright majority after a strong challenge from a coalition of left-wing parties in National Assembly elections.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s left-green alliance finished neck and neck with Mr Macron’s Ensemble (Together), in terms of votes cast in Sunday’s first round.

The president faces a battle in next week’s second round to win 289 seats and keep his majority.

Turnout was a historically low 47.5%.

Within half an hour of the first projection, a sombre Jean-Luc Mélenchon announced his alliance was in the lead: “The truth at the end of the first round is that the presidential party is beaten and defeated.” He called on voters to turn out in force next Sunday “to reject definitively the disastrous policies of Mr Macron’s majority”.

Centrist Emmanuel Macron won a second term in April, but without a majority in the Assembly he will struggle to push through reforms. He intends to raise gradually the retirement age from 62 to 65, while Mr Mélenchon vows to lower it to 60.

Although Ensemble won 25.75% of the vote, marginally ahead of the left’s 25.66%, it was still projected to dominate the National Assembly. TF1 pollster Ifop gave Ensemble 275 to 305 seats, with the green-left alliance on 175-205. Ipsos for France Télévisions said Mr Macron’s alliance was heading for a lower 255-295 seats and the left 150-190.

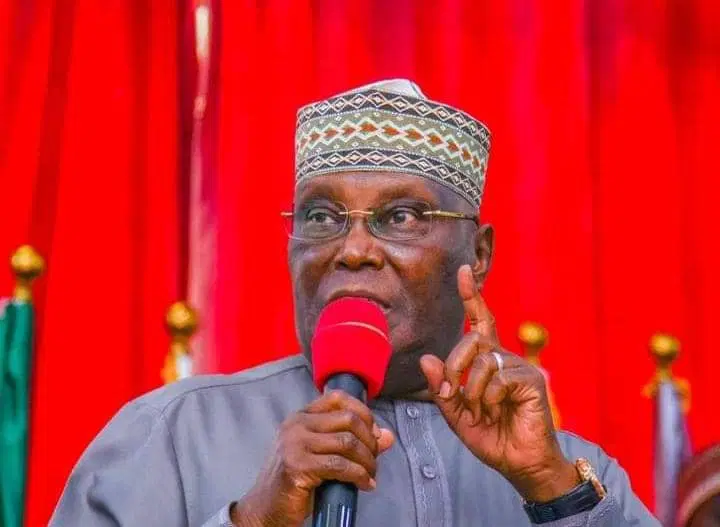

IMAGE SOURCE,EPA Image caption, The left-wing coalition leader voted on Sunday morning in Marseille

IMAGE SOURCE,EPA Image caption, The left-wing coalition leader voted on Sunday morning in MarseilleTurnout was the lowest in modern French history. Many voters clearly decided to take advantage of the sunny weather across France, with temperatures in Paris hitting 27C. But so far the election campaign has largely failed to spark into life.

Mr Mélenchon has proved the exception, leading a vigorous campaign since he came a close third in the presidential election. He has built an alliance called Nupes, made up of his own far-left party France Unbowed, the Socialists, Communists and greens – with the slogan “Mélenchon prime minister”.

His aim has been to stop the president winning the majority he needs across France’s 577 constituencies. On top of lowering the retirement age, Nupes vows to freeze prices on 100 essentials and create a million jobs.

Meanwhile, Mr Macron has spent the intervening weeks since he won a second term in building a new government under Elisabeth Borne, as France grapples with rising inflation and a cost of living crunch.

The prime minister said the government had one week to convince voters and win a majority. Pointing to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, she said “we cannot risk instability”; France’s values were at risk, she said: “We alone have a project of coherence and responsibility.”

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS Image caption, Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne is one of 15 members of the government being challenged in this election

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS Image caption, Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne is one of 15 members of the government being challenged in this electionMs Borne is one of 15 ministers who have to win their seats to stay in government. And as each constituency is an individual local race, this election is played out over two weeks. Amélie de Montchalin, the minister in charge of green transition, faces a battle to survive as an MP, as does Europe Minister Clément Beaune. Former Macron education minister Jean-Michel Blanquer was an early casualty, losing out in the Loiret area to the south of Paris.

Unless a candidate wins more than 50% of the vote based on a quarter of the electorate, the race culminates in a run-off next Sunday, involving the top two candidates and anyone else who wins 12.5% of the vote.

One of Mr Mélenchon’s closest colleagues, Manuel Bompard, was only denied outright victory in the first round in Marseille because of a low turnout. Green leader Julien Bayou also came close to winning through in the first round.

Far-right Marine Le Pen, who was runner-up in the presidential elections, was delighted with her party’s performance. Her National Rally won 18.68% of the vote with a projected 15-30 seats, higher than her current number of eight. Another far-right leader, Éric Zemmour, was knocked out of the election in the first round.

The mainstream right, which fared badly in the April vote, has focused its campaigning locally. Despite winning only 10.42% of the vote, the Republicans could win 45 to 65 seats.

The fact that one in two French voters had stayed away from the ballot box on Sunday was worrying, said political scientist Olivier Rouquan. People felt they had already expressed their opinions in the presidential election, he believed.