“There was water everywhere, but not a single drop to drink.”

That is how Ronju Chowdhary described the scene outside her house on Saturday. She lives in Udiana, a remote village in the north-eastern Indian state of Assam, which has been hit by severe floods.

It had been raining incessantly, she remembers. The water rose so quickly that the streets were completely submerged within hours. When the water entered their home, she says the family huddled together in darkness trying to keep themselves safe.

Two days on, the family is still marooned in their house – now resembling a lonely island – amid a sea of water.

“We are surrounded by flood water from all sides. There’s hardly any water to drink. Food is running short too. And now I hear that the water levels are further rising,” Ms Chowdhary says. “What will happen to us?”

Unprecedented rainfall and flooding has left behind a trail of destruction in Assam, submerging villages, destroying crops, and wrecking homes. Authorities say that 32 of its 35 districts have been affected, killing at least 45 people and displacing more than 4.7 million over the last week.

Heavy rains have also lashed neighbouring Meghalaya state, where 18 people have died over the last week. In Assam, the government has opened 1,425 relief camps for the displaced, but authorities say their job has been complicated by the sheer intensity of the disaster. Even the rescue camps are in a dismal state.

“There is no drinking water in the camp. My son has a fever but I am unable to take him to the doctor,” says Husna Begum, also a resident of Udiana. When water reached her home on Wednesday, the 28-year-old swam through the torrent in search of help. She is now sheltering in a rickety plastic tent with her two children.

“I have not seen something like this before. I’ve never seen such huge floods in my life,” she says.

Floods routinely wreak havoc on the lives and livelihoods of millions living near the fertile riverbanks of the mighty Brahmaputra river, often called the lifeline of Assam. But experts say that factors like climate change, unchecked construction activities and rapid industrialisation have increased the frequency of extreme weather events.

This is the second time this year that Assam is grappling with such fierce floods – at least 39 people were killed in May. The state has already recorded rainfall 109% above average levels this month, according to the weather department. And the Brahmaputra is flowing above the danger mark at many places.

Residents and authorities the BBC spoke to describe the latest deluge as one of “biblical proportions” – one that has altered the social and economical fabric of the state.

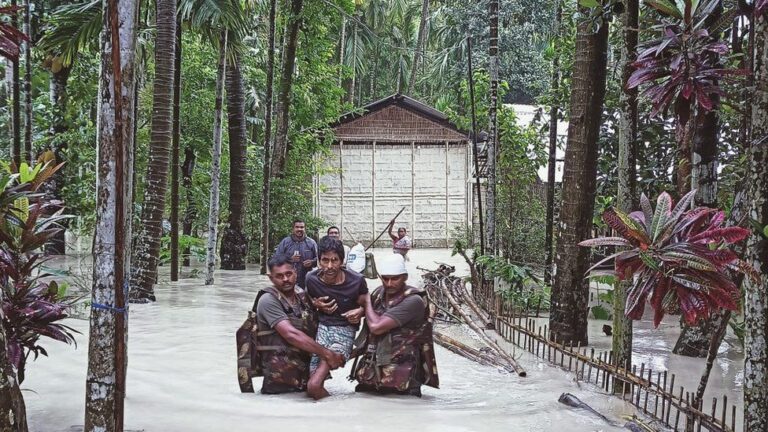

“The situation is particularly alarming this time. Apart from the team of the National Disaster Response Force (NDRF), we have also deployed the army to aid the rescue operations,” says Javir Rahul Suresh, a sub-divisional officer in Rangiya city.

“At this point, our priority is to save lives.”

Entire settlements have been engulfed by rushing waters, almost resembling a huge river that had formed overnight.

In Guwahati, the main economic centre of Assam, neighbourhoods have been reduced to rubble. Lush fields where rice and paddy normally grew have turned into vast swamps of mud and debris.

Back in Udiana, there are no schools, hospitals, temples or mosques in sight – just water. People travel by boats made of banana leaves and bamboo sticks. Others just swim through the brown, green brackish waters despondently, their eyes lighting up at the sight of rescuers, whose bright orange uniforms are visible from a distance.

The damage is particularly alarming in Kamrup Rural district, where hundreds of people are still reportedly trapped in their houses.

Siraj Ali, 64, says that when the water swept into his village and destroyed everything, he was scared for his life. Yet he stayed on, in a house which is now partly submerged under water, to guard his belongings and “a life-time of memories”.

He said he sent his children to a roadside shelter camp, while he waited for help to reach him. But no one has come so far.

“I am surrounded by water but I have no water to drink. I don’t have food. I have been starving for three days. What to do and where do I go?” he asks, his eyes welling up with tears.

Mr Ali now finds solace in the company of his neighbour Mohammad Rubul Ali, a daily-wage worker, who also decided to stay back to protect his house – a small hut that he painstakingly built.

“Every purchase was like a milestone for me – the cycle, the bed and the chairs. But now nothing is left. The flood took everything away from me,” Mr Rubul says.

Authorities admit that they have been unable to provide drinking water and food to every flood victim.

“It is still a challenge for us to reach some areas which have been completely cut off. Our road network reaching there has been completely ruined in the water,” Mr Suresh says.

Experts say that while climate change has complicated the state’s longstanding efforts to improve its response to flooding, there are several other factors at play.

“There is no doubt that the flood situation this time is very serious and the frequency of rains is increasing significantly,” says Jayashree Rout, an environmental science professor at Assam University. “But before linking it entirely to climate change, we need to take into account human-related factors like deforestation.”

Prof Rout says there’s an urgent need to stop the felling of big trees, especially near rivers as the roots of these trees have a lot of capacity to hold water.

But people like Ms Chowdhary have no time to analyse the reasons.

On Saturday, as the sun dripped over the cloudy horizon in Udiana and dusk crept over the sky, she sat outside her half-submerged house, visibly worried.

“Till now, no one has given us anything in the name of relief,” she says. “Is anyone even coming?”

BBC