Former Ukrainian captives say they were subjected to torture, including frequent beatings and electric shocks, while in custody at a detention facility in south-western Russia, in what would be serious violations of international humanitarian law.

In interviews with the BBC, a dozen ex-detainees released in prisoner exchanges alleged physical and psychological abuse by Russian officers and guards at the Pre-Trial Detention Facility Number Two, in the city of Taganrog.

The testimonies, gathered during a weeks-long investigation, describe a consistent pattern of extreme violence and ill-treatment at the facility, one of the locations where Ukrainian prisoners of war have been held in Russia.

Their allegations include:

- Men and women at the Taganrog site are repeatedly beaten, including in the kidneys and chest, and given electric shocks in daily inspections and interrogations

- Russian guards constantly threaten and intimidate detainees, some of whom have given false confessions which were allegedly used as evidence against them in trials

- Captives are constantly left under-nourished, and those who are injured are not given appropriate medical assistance, with reports of detainees dying at the facility

The BBC has been unable to independently verify the claims, but details of the accounts were shared with human rights groups and, when possible, corroborated by other detainees.

The Russian government has not allowed any outside bodies, including the United Nations and the International Committee of the Red Cross, to visit the facility which before the war was used exclusively to hold Russian prisoners.

Russia’s defence ministry did not respond to several requests to comment on the allegations. It has previously denied torturing or mistreating captives.

The prisoner swaps between Ukraine and Russia are a rare diplomatic achievement in the war and more than 2,500 Ukrainians have been released since the start of the conflict. Up to 10,000 captives are believed to remain in Russian custody, according to human rights groups.

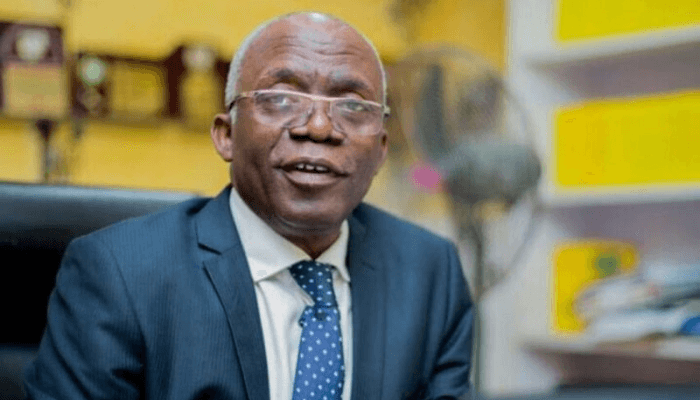

Dmytro Lubinets, Ukraine’s human rights ombudsman and one of the officials involved in exchange negotiations with Moscow, said nine in every 10 former detainees claimed they had been tortured while in Russian captivity. “This is the biggest challenge for me now: how to protect our people on the Russian side,” Lubinets said. “Nobody knows how we can do it.”

Last September, Artem Seredniak, a senior lieutenant, had already been in Russian captivity for four months when he and about 50 other Ukrainians were transferred to Pre-Trial Detention Facility Number Two. They travelled in the back of a truck for hours, without knowing where they were going, blindfolded and tied to each other by their arms, like a “human centipede”, Seredniak told me.

On their arrival in Taganrog, he recalled, an officer greeted them: “Hello boys. Do you know where you are? You’ll rot here until the end of your lives.” The captives remained silent. They were escorted inside the building, Seredniak said, had their fingerprints taken and clothes removed, were shaven and forced to shower.

At every step, guards at the facility, who carried black batons and metal bars, beat them in the legs, arms, or “anywhere they wanted”, Seredniak said. “It’s what they call ‘reception’.”

BBC